Anyone who has marvelled at the complexity of Mughal monuments or simply savored the refreshing vibes around a Goan house knows that there is something magical about artistically designed spaces. Just like a painting or sculpture, architecture too has the ability to surprise, transform and draw the observer into its depths and details.

Since the land art movement of the 1960’s, the art and architecture world has woken up to the ecological impacts of the marvels created by contemporary artists. Expanding beyond known limits, architects and designers are sketching out more innovative ways to build structures with special attention towards the conscious use of material, labour and natural surroundings.

There are numerous examples of these pioneering creators and here are some of our favourites! This week we turn our lens towards the architects who have broken all preconceived notions of constructing buildings seamlessly merging them with nature. Based in India, their unconventional works remain examples of an effortless blend of eco-friendly elements and novelty.

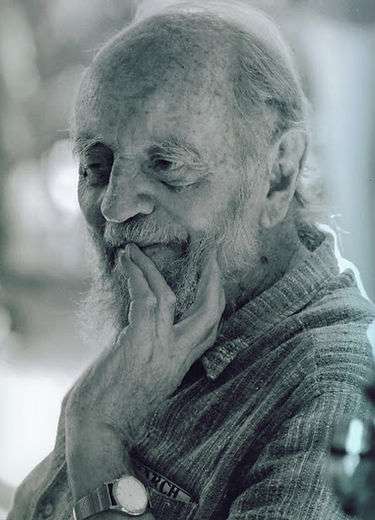

The Gandhi of Architecture – Laurie Baker

When it comes to sustainable architecture, one of the first names that comes to our mind is the British-born architect Lawrence Wilfred “Laurie” Baker. Revered as the pioneer of organic and sustainable architecture in India, he was a man of many beliefs and principles that extended beyond his role as an architect. The hallmarks of Laurie Baker’s practice were marked by his quest for the perfect balance and harmony between man-made architectural structures and nature. His buildings showcased fine designing, tinged with just the right amount of tradition and modernity!

Trained as an architect at the Birmingham Institute of Art and Design, Baker spent a long time in his youth as an anaesthetist for the British Army during the Second World War. A curious twist of fate led him to cross paths with Mahatma Gandhi in 1943. Moved by Gandhi’s ideals of humanitarianism and non-violence, Baker joined the World Leprosy Mission as an architect in 1945. With the advancement of leprosy medicines, he was responsible for turning asylums into treatment centres for the afflicted patients.

Most of Baker’s practice was based in Pithoragarh and Trivandrum, where he demonstrated a fusion of simplicity, functionality and social conscience in his works. “I don’t like deceit. A building should be truthful.” Sticking by these words, he introduced improvisation along with his artistic idiosyncrasies in the mix! If looked at closely, we can find numerous anomalies in his structures, which add to their vernacular character and originality.

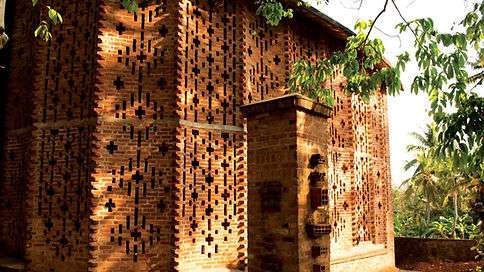

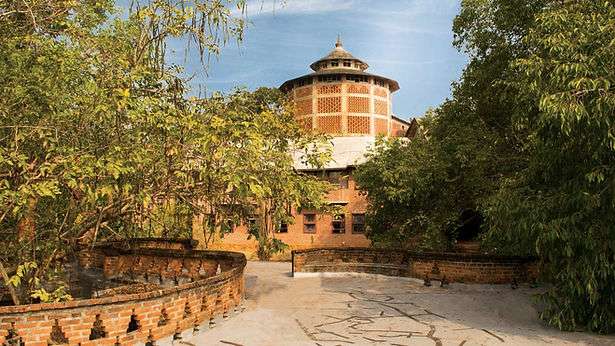

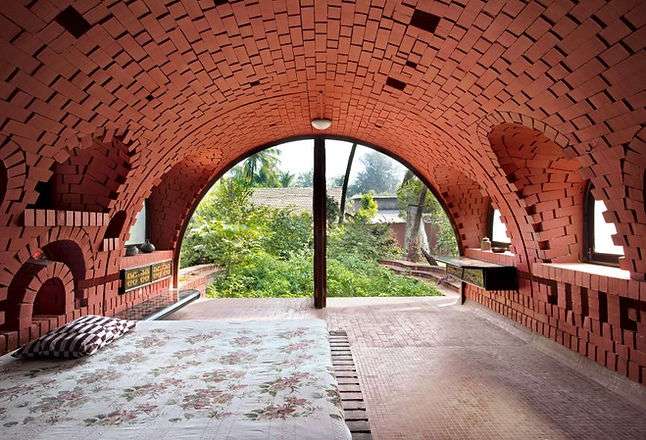

His designs come across as an interplay between geometry and minimalism, characterized by brick jaali walls often flaunting curves, arched doorways and a noticeable lack of extravagance in ornamentalism. The element that stands out in Baker’s buildings is the lack of color. His love for bricks and their raw appearance are reflected in the absence of any additional modification or layering of the outward walls. Causing minimal damage to the environment, he brought to his structures an unparalleled design philosophy and a rare aesthetic sensibility, creating a bridge between ecology and architecture.

Some of his well-known works include the Centre of Development Studies, Hamlet (his residence in Trivandrum), Indian Coffee House and Laurie Baker Centre for Habitat Studies. So if you ever happen to visit Kerala, don’t forget to check out these iconic creations!

Fusing architecture, art and nature with Didi Contractor

Regarded as the ‘dame’ of building homes in indigenous styles, Delia Kinzinger (popularly known as Didi Contractor) grabs our attention with her unorthodox tryst with architecture! Formally trained in art and design, she was a self-taught architect driven by her own passion to create sustainable housing using cost-effective methods. Based in Sidhbari (Kangra Valley), Didi had carved out her own place in modern Indian architecture with the environment’s best concerns on her mind.

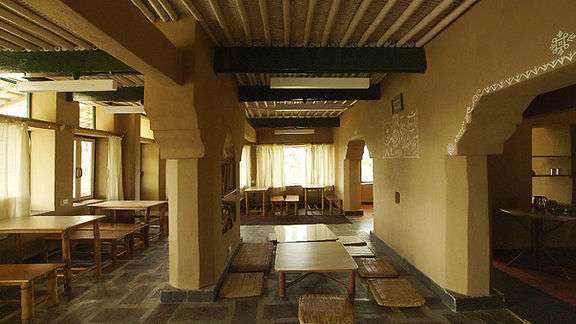

After she relocated to Sidhbari (Kangra Valley), she began her on-field endeavours with sustainable architecture and organic interior design. Faced with budgetary constraints and the challenges of constructing on a contoured site at Sidhbari, Didi used locally sourced materials for her structures. Her ingredients for a perfect abode included bamboo, mud, slate, stone and wood, along with different proportions of shredded waste paper, cow dung, and adhesive mixes for wall plasters.

Keeping the construction costs in check, her methods reduced the building’s embodied energy and the hazards towards the natural surroundings. Though her structures contained numerous traits of traditional methods of building structures, her pragmatic and artistic orientation brought a modern touch to everything she designed. Illuminated interiors, minimal furniture, and gently curved and spacious staircases formed the backbone of her style, giving the building a salient character.

Didi’s almost 30-year long practice was marked by her ambition to create more than just ecologically sound structures. She was always conscious of how her buildings would evolve with time and establish a symbiotic relationship with their residents. Going beyond the label of an architect and designer, she established herself as a visionary environmentalist winning the Nari Shakti Puraskar in 2016.

Flowing out and within nature with Nari Gandhi

‘Land is the purest form of nature, and buildings grow towards the light like a plant’ – Nari Gandhi

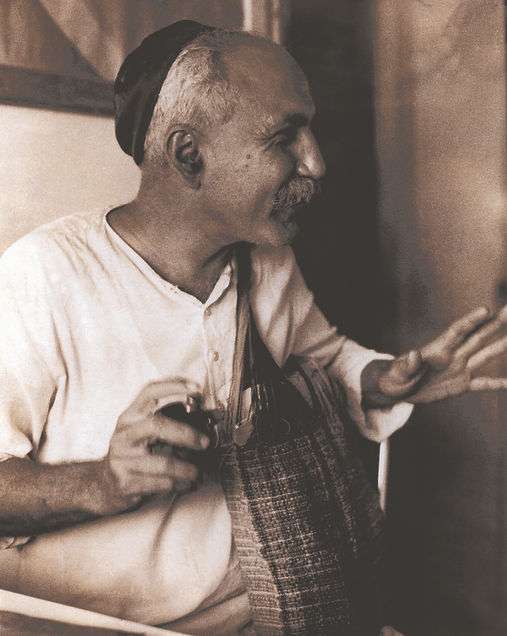

Nariman Dossiman Gandhi– an icon who remains the embodiment of extraordinariness tinged with eccentricity when it comes to organic architecture in modern India! Known for his broadscale and experimental thought process, his architectural style was adorned by a quirky play of geometrical structures, open spaces and a complete disregard for architectural norms.

Always dressed in white khadi kurta pajamas and Kolhapuri slippers, Nari led a simple, minimalist life and strictly avoided any kind of public attention. Led by his Zoroastrian beliefs, he took inspiration from nature and its immanent tranquility.

Nari Gandhi was notorious for his penchant towards swimming in uncharted territories, which he had done throughout his life. After the completion of his architectural studies from Sir J. J. School of Architecture, he travelled to the US to apprentice with Frank Llyod Wright at the Taliesin for 5 years, after which he tried his hand at pottery. Due to his multiple skill sets and an affinity towards building with natural materials his creations were pieced together from a little of everything- brick, stone, wood, pottery, glass.

Nari’s form was drawn from Wright’s idea of ‘flowing spaces’, inclusive of the local climate and culture. His buildings were created in a smooth tangent to the surroundings, where the trees and the constructed spaces moulded into each other. He spent an inordinate amount of time with the craftsmen on his site due to his strong dislike towards formal office etiquettes. The daunting side of Nari’s character was evident from the lack of any prior design or sketch of a building which was improvised as it was made.

Nari’s works demonstrated an assortment of contradictory shapes, custom-made furniture, erratic perforations in the walls, arched doorways, semi-open spaces; creating a myriad play of light and shadows. He built the houses while keeping ample space for the trees and other natural elements, allowing them to evolve along with the structure.

These buildings emerged from his bohemian traits that turned them into static but living organisms. Some of these well-known works include Korlai Bungalow, Revdanda House, Beach House and more, mostly centered in and around Mumbai. So if you ever happen to be in Mumbai, walk into one of these spaces and who knows, it might just stir the maverick creator inside you!

Bijoy Jain: On creating with empathy

Bijoy Jain is known for creating structures that resemble scenes straight out of a Luca Guadagnino film – carrying traces of elegance, tranquility, subtlety and nostalgia. So much of what Jain has envisioned and created draws from his own personal experiences and tragedies. Familiar with the feeling of loss, he brings to his structures a sense of refuge and a dialogue within the spaces.

A student of abstract artist and the architect Richard Meir, Jain’s attention to detail spans from his tasteful crafting of a single chair to building an expansive bungalow. At the heart of his practice lies his motto of creating a ‘space’ rather than a building; with empathy towards the natural space and elements where it is being constructed. With a careful study of the existing light, wind conditions, trees and water bodies, he moulds his structures into these surroundings.

Driven towards fusing design with sustainability, Jain employs indigenous labourers and construction methods that are best suited to the environment. He maintains an ethical approach towards architecture, avoiding the import of materials or experts to reduce the carbon cost behind his buildings. Jain’s ambition to stretch the limits of his imagination reflects in the way he mixes up locally sourced materials with modern design elements, keeping their respective outlook intact.

Bijoy Jain’s architectural marvels go beyond the confines of India, reaching the reputed Venice Architecture Biennale, the Victoria and Albert Museum, Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, Japan and more.

Across India’s metropolitan cities and regional spaces, these stalwarts have left their products of conscious design sense. These structures remain proof that at times a handful of commonplace materials is all it takes to build a remarkable home!

For more such stories on the fusion of materiality, art and design, read our blog on Artists Using Mundane Materials to Create Extraordinary Works of Art.