Contemporary South Asian art is often anchored in questions of identity and politics. Vishakha Jindal, however, has carved out a more playful, universalist niche within this dynamic landscape. Based in Mumbai and also known by the moniker ‘Vikiki’, she moves fluidly between painting, paper cutouts, textile art, and sculptural objects. Her practice is deeply personal yet intuitively accessible, treating art-making as a process of exploration and play, led by curiosity rather than dogma.

Vishakha describes her work as “an invitation for anyone and everyone to come and interact with it,” emphasizing an open-door philosophy that breaks down boundaries between art and viewer. In a world where contemporary art can often feel shrouded in jargon and exclusivity, she champions accessibility, aspiring to a visual language that “should be accessible to each and every one.” This positions her at the forefront of a new wave of South Asian artists determined to democratize art without dumbing it down.

Her journey began with a camera and an eye for the unexpected, shaped by a decade of self-taught photographic experimentation. As her instinct for visual storytelling evolved, it naturally flowed into painting. A move to Mumbai’s space-conscious apartments prompted her to embrace more immediate and compact media. What began as an attempt to merge photography with paint soon blossomed into a full-fledged painting practice, one driven by intuition over fixed plans, often involving putting up canvases “every day and just painting.”

Two guiding principles emerged in this new phase: the idea of play and Taoist philosophy. Vishakha’s childhood was split between carefree play and periods of difficulty, making play both a joyful memory and a vital release. Alongside that is Taoism. Its embrace of stillness, presence, and non-interference became central to her artistic process. Painting for her is meditative, a quiet act of flow. In a delightfully wry observation, she even suggests that as A.I. automates life’s drudgery, humans will reclaim play. Her worldview, at once childlike and sagely, forms the philosophical backbone of her practice. Her work echoes Taoism’s trust in spontaneity and natural evolution, steering clear of fixed outcomes and embracing each emergent form as it arises.

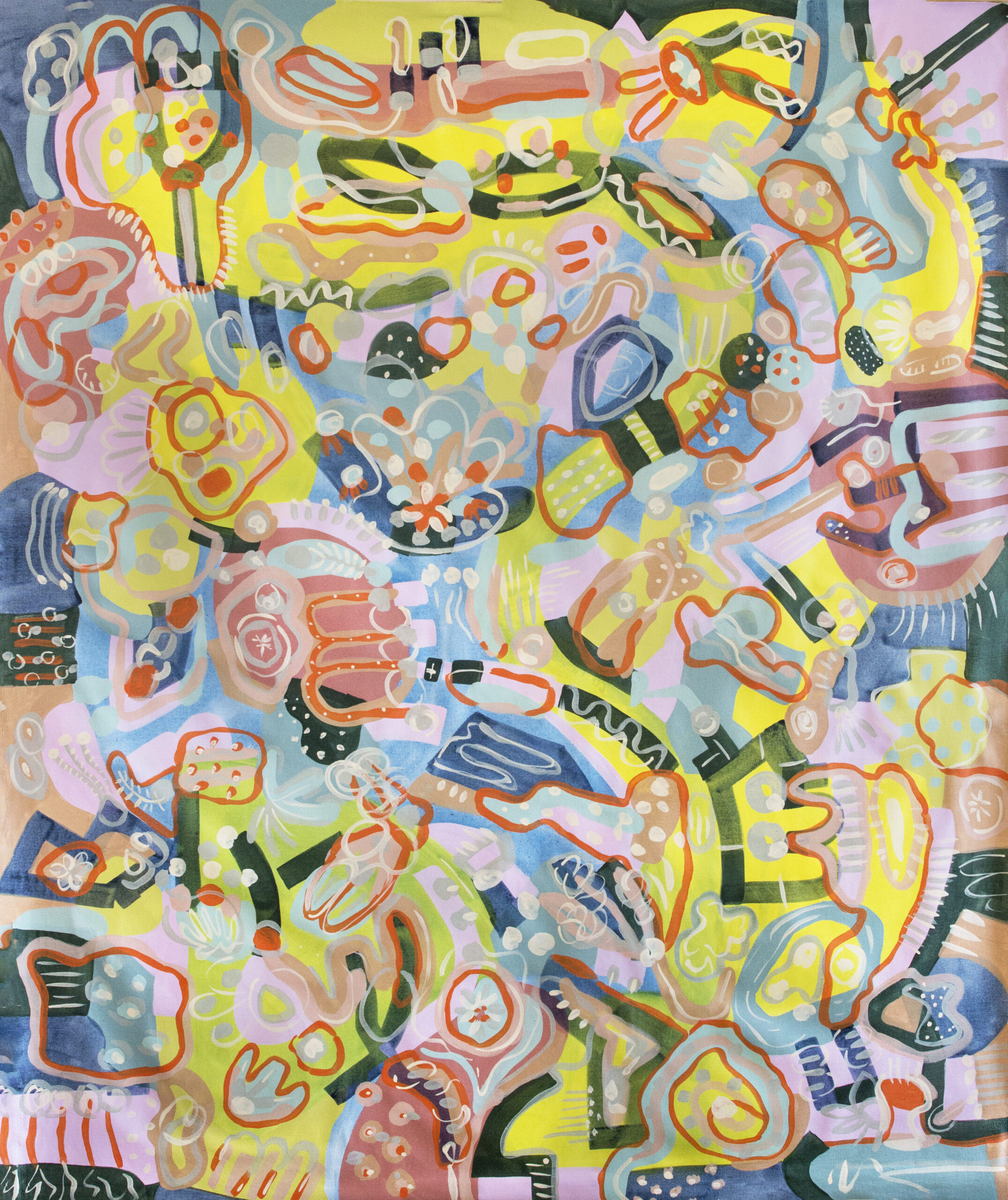

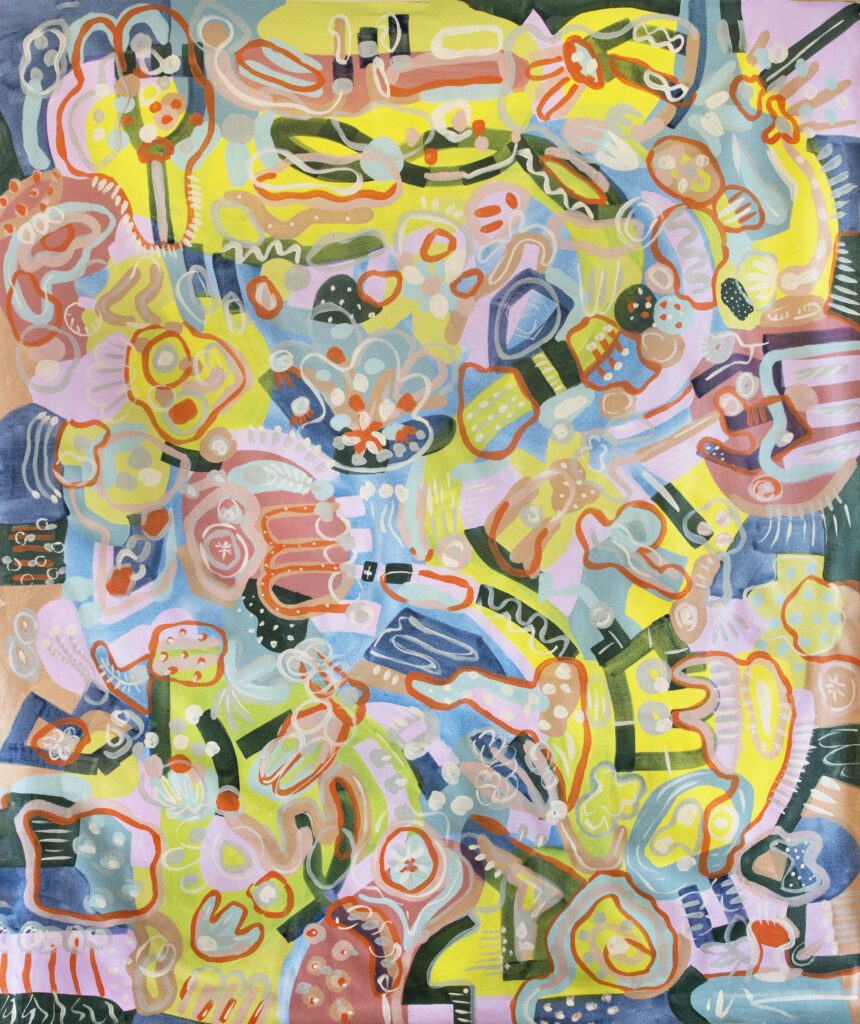

A defining idea in her practice is the “visual habitat.” Her paintings resemble living ecosystems: fields where colors, textures, and shapes interact dynamically. Inspired by organic patterns like leaf formations or ocean currents, she avoids direct replication and instead channels their underlying logic. Her compositions evolve as abstract communities of form, shaped by instinct and attuned to natural harmony. She likes her approach to an alphabet: “like writing, where different alphabets make words, and the story kind of emerges.” But the story, she insists, is co-authored by the viewer. In this way, each painting is a playground of forms, a site for collaborative imagination. The act of viewing isn’t passive here. Instead, it’s a realm ripe for active meaning-making.

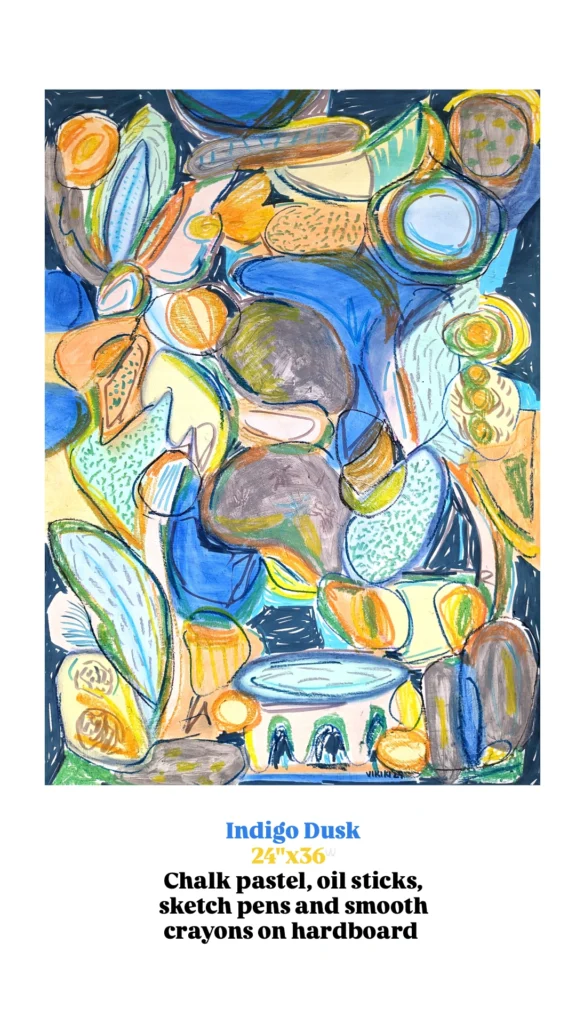

Vishakha Jindal, My subconscious mind underwater, 12×12 inch, Acrylic on Hardboard, 2020

While painting anchors her practice, Vishakha’s curiosity has pushed her into new territories: textiles, paper, and three-dimensional objects. Her time at Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology in Bangalore nurtured this experimental spirit and love of material diversity. She constantly shifts between surfaces and techniques depending on what feels right for the idea at hand. On large canvases, she may build layers with watery washes and sponged pigments, letting the fabric help shape hazy, organic textures. On hardboards, crisp brushwork takes precedence, serving the fluidity she values in her process.

Textile art marks one of her most tactile and engaging expansions. Collaborating on hand-tufted rugs, she translated her abstract forms into wool and silk. Rugs, she says, are “all about tactility,” inviting people to touch and feel. The interaction with texture, running one’s hand across a surface, adds a new, haptic dimension to her visual language. The raised pile creates a literal topography, and adapting her designs to weaving constraints opens up new creative challenges.

Paper, too, for her, has become a kind of sculptural terrain. In recent years, she has created painted paper cutouts, slicing up her own paintings and recomposing them into collages. “The act of making something and then cutting it up to make something else is very freeing,” she says. This process of fragmentation and renewal brings constant surprises. Similarly, her “No Paint” series challenged her to leave acrylics behind in favour of crayons, chalk, oil pastels, and sketch pens, rediscovering the thrill of raw, instinctive mark-making.

Lately, she’s ventured into sculpture, developing a series of small, painted, interlocking forms: her “objects of play.” These are meant to be rotated and explored from different angles, each revealing a new interaction of shape and color. The idea was sparked by the expressive power of color palettes: how just a few hues can evoke a memory, mood, or imagined place. Building these pieces has involved deep dives into prototyping and material research, but the joy lies in the unpredictability of the process. As always, not knowing what comes next is part of the appeal.

At the core of this expansive, ever-evolving practice is a single motive: to craft a visual language that is deeply personal yet legible to everyone. In a contemporary art world that can skew toward intellectual opacity, her work stands out for its joy and openness. She wants art to be perceived as a universal playground, where shapes and colors speak across boundaries.

Her commitment to accessibility is also a quiet critique of the Indian art world’s dominant themes. While she recognizes that socially or politically charged content is often favored, she charts a different path, centered on exploration, imagination, and togetherness. This belief infuses every part of her practice, from her playful compositions to her push for more accessible conversations around art. Her work doesn’t require specialist knowledge; it invites intuitive responses. By keeping her work non-linear and non-prescriptive, she ensures there’s never just one way to see or understand it. In this, she offers a refreshing, emotionally resonant alternative within the evolving landscape of South Asian art, one that proves playfulness and profundity can happily coexist.