Some of history’s most famous paintings are more than oil on canvas rendered through sheer skill and mastery. They are maps and puzzles hiding secrets, revealing inadvertent clues about the painter or giving rise to inexplicable mysteries. Join us as we open up a virtual time machine to probe the concealed details behind the world’s most famous paintings.

The Old Guitarist, Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso met Carlos Casagemas in 1899 and the two quickly became fast friends. In 1900 they moved to Paris together to follow their dreams of becoming famous artists. But Carlos’s depression and mood swings, combined with his failed love affair with Germaine Pichot led him to commit suicide just a year later. This tragedy is what kickstarted Picasso’s Blue Period.

Aside from Casagemas’s death, Picasso had other reasons to despair. He had sunk into a deep bout of depression himself which was to last several years. He was living in poverty. The initial reaction to his works in France had been warm. But as he began painting downtrodden and morose subjects in monochromatic shades of blue, a reflection of his state of mind, the public turned away from his art and his already depleting finances took a severe hit.

In The Old Guitarist, painted in 1903, a gaunt and starved old man in tattered clothing clings to a brown guitar. It’s theorized that Picasso identified deeply with the guitarist, holding on to his art at a time of utter despair and misery in his life.

Picasso was forced to salvage and reuse canvases for his paintings. Infrared imaging and expert analysis have revealed that there exist at least two more paintings beneath The Old Guitarist. There’s a young mother with a child kneeling at her right and a calf or sheep at her left side. There’s also an old woman with her head bent forward. Why Picasso abandoned these subjects is not known, but their spectre haunts this most iconic work of his.

La Primavera, Sandro Botticelli

Botticelli’s La Primavera has puzzled viewers about the true nature of its meaning for centuries. Painted around 1481 – 1482 to celebrate the marriage of a powerful Medici scion, the fact that it celebrates the themes of spring – love, fertility, renewal, joy – seems apt for the occasion. But the characters Botticelli chose to cast together in the same frame has led to hundreds of theories, some convincing and others more far-reaching, over the years.

There’s Venus, the Goddess of Love, at the centre. On the far right is Zephyrus, the spring wind, chasing the nymph Chloris. When he catches her, she transforms into Flora, the goddess of Spring. On the far left is Mercury chasing away the winter clouds. The Three Graces, representing the virtues of Chastity, Beauty and Love, dance next to him. Above them is Cupid doing what he does best – naughtily shooting arrows of love into the crowd.

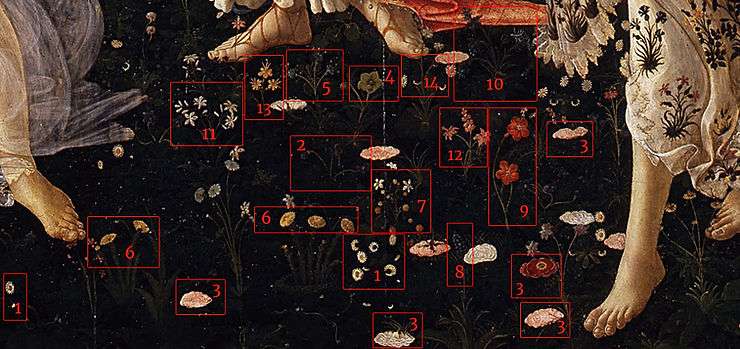

But it’s not the Pagan references that Botticelli painted in the bastion of Catholic power that we refer to when talking about the hidden details in La Primavera. It’s the 200 plus species of plants and flowers scattered throughout the painting that takes our breath away. The impossible care and minute restraint with which they have been brought to life speak volumes of the mastery of Botticelli’s skill.

There are about 500 flowers strewn throughout the meadow – rose, poppy, jasmine, chamomile, daisies, buttercups, violets, chrysanthemums and many more. While our horticulture knowledge may not reach such depths, we don’t need a degree in botany to appreciate it. The next time you feast your eyes upon the La Primavera, tear your gaze away from the frolicking gods and goddesses and see how many flowers can you find.

Arnolfini Portrait, Jan van Eyk

The riddles of the Arnolfini Portrait continue to mystify seven hundred years after its creation. At first glance, it seems to be a certificate of marriage of a wealthy couple. The male subject is Giovanni Arnolfini, a wealthy Italian merchant settled in the Belgian city of Bruges, then a part of the Dutch Burgundy. He wants people to know how wealthy he is. Ergo the fur trimmed robes, stained glass windows, finely woven rugs, fancy trophy dog, designer sandals, chandelier and his wife’s emerald gown which can dress ten bay windows.

The artist reflected in the mirror, and his signature on the wall above, seems to be witnessing the union of the couple. The unblemished mirror, which is decorated with scenes from the Passion of the Christ, signifies piety. The dog represents fidelity. The cherry tree outside is a symbol of love. The oranges and the carved figure of St. Margaret, the patron saint of childbirth, signify fertility. Mrs. Arnolfini looks pregnant, even though she actually isn’t. A little good luck premonition perhaps.

All in all, it looks like a happy, if formal, picture of domesticity between an uber-rich medieval husband and wife whose main agenda seems to be producing Arnolfini junior. But which wife?

The portrait was completed in 1434. Giovanni’s wife Constanza died in 1433, possibly during childbirth. It seems macabre to celebrate fertility and pregnancy if your wife died in childbirth. It’s even more puzzling as to create a pictorial wedding certificate eight years after the event took place. Giovanni and Constanza were married in 1426.

Art historian Erwin Panofsky had confidently concluded that the painting was to mark the wedding of Giovanni Arnolfini and Giovanna Cenami. But the discovery of a document in 1990 revealed that that marriage took place in 1447, some 13 years after the painting was completed and six years after Van Eyk’s death.

While these questions may never be satisfactorily answered, the painting itself is a gem of revelations upon close scrutiny. The way the convex mirror opens up the space and adds extra subjects had never been done before. The gleaming surfaces of the brass chandelier reflects the surroundings with photographic accuracy. Van Eyk loved to investigate the effects of light and oil painting allowed him to experiment with that.

The next time you look up famous artworks online or visit an European museum to check out its treasures, remember to take your monocle. The beauty of first impressions is just a prelude. The real story goes way, way deeper.

The Night Watch by Rembrandt van Rijn

Rembrandt’s most famous painting is not actually called The Nightwatch. Also, it’s set in the daytime. To be fair if a painting was called Militia Company of District II under the Command of Captain Frans Banninck Cocq or The Shooting Company of Frans Banning Cocq and Willem van Ruytenburch then we too would jump on the bandwagon of whoever it was who decided to colloquialise it to The Night Watch. It only acquired that moniker in the 1790s, 150 years after its creation, because of the way the varnish had darkened.

When Rembrandt died in 1669, he was penniless despite the fact that he had enjoyed immense wealth and success courtesy of his art. In a life plagued by tragedy and bankruptcy, many believe that it was The Night Watch which was his death knell.

The artwork is a life-sized depiction of Amsterdam’s civic militia companies. Filmmakers like Peter Greenaway and Alexander Korda have made movies justifying the conspiracy theories that The Night Watch reveals a murder plot concerning the members of the militia that led to Rembrandt’s ruin. More believable reasons include that the militia men did not like the way the artist portrayed the scene, diverging significantly from the norms of the time.

Whatever the reason, twenty years after he was buried, the church dug up Rembrandt’s remains and discarded them. It was only in 1909 that he finally got a headstone. Meanwhile The Night Watch hangs tall and proud in Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum, enthralling viewers with its mysteries and motifs five hundred years after its creator’s death.