“For now at last we are looking at the same picture; we are seeing with you the same dead bodies, the same ruined houses.”

–Virginia Woolf (‘Three Guineas’, 1938)

Human history has constantly and cyclically witnessed its fair share of disaster. Although we sometimes forget that we are, in fact, part of a delicate and complex ecological system, ever so often a natural cataclysm comes around to remind us of this. In the meantime, our deep recognition of art as inherent to human nature has meant, obviously, that art history is thoroughly peppered with depictions of these disasters—a pathway to channel the fear, the unpredictability of nature that accompanies the experience of human existence.

Let’s take a look at how nature’s fury has found its way into visual art, from the contemporary to the classical.

On a winter morning in 2018, Olafur Eliasson’s Ice Watch was unveiled outside Tate Modern, on the banks of the River Thames. This was the third in a series of the poignant installations which had previously been witnessed in Copenhagen and Paris. The clock formation was composed of large ice blocks that had been harvested from a fjord near Nuuk, Greenland. These ice blocks—perhaps centuries, or millenia old—had once been a part of the Greenland ice sheets, only to be cast off from them due to global warming. The artwork carried an invitation for viewers to touch, play, even taste the melting ice, as they experienced a tangible encounter with the consequences of our actions. Best articulated by Eliasson himself, “It lets them see and feel what we are losing. I really hope that Ice Watch can create feelings of proximity and presence, and make us engage.”

Echoing the sentiment of Ice Watch, Marzia Farhana’s Ecocide and the Rise of Free Fall was the culmination of several weeks spent collecting discarded objects and commodities that had been washed away in the Kerala floods of 2018. The four-room exhibit at the Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2018 featured these objects as a nod to the “irresistible fall” that we find ourselves trapped in, and was a call for humankind’s relationship with the environment to be reimagined through a decolonising process. “I am trying to showcase how everyone is suffering in the violent conditions of a world where humans have become more of machines and machines have become more of humans,” said the Bangladeshi artist.

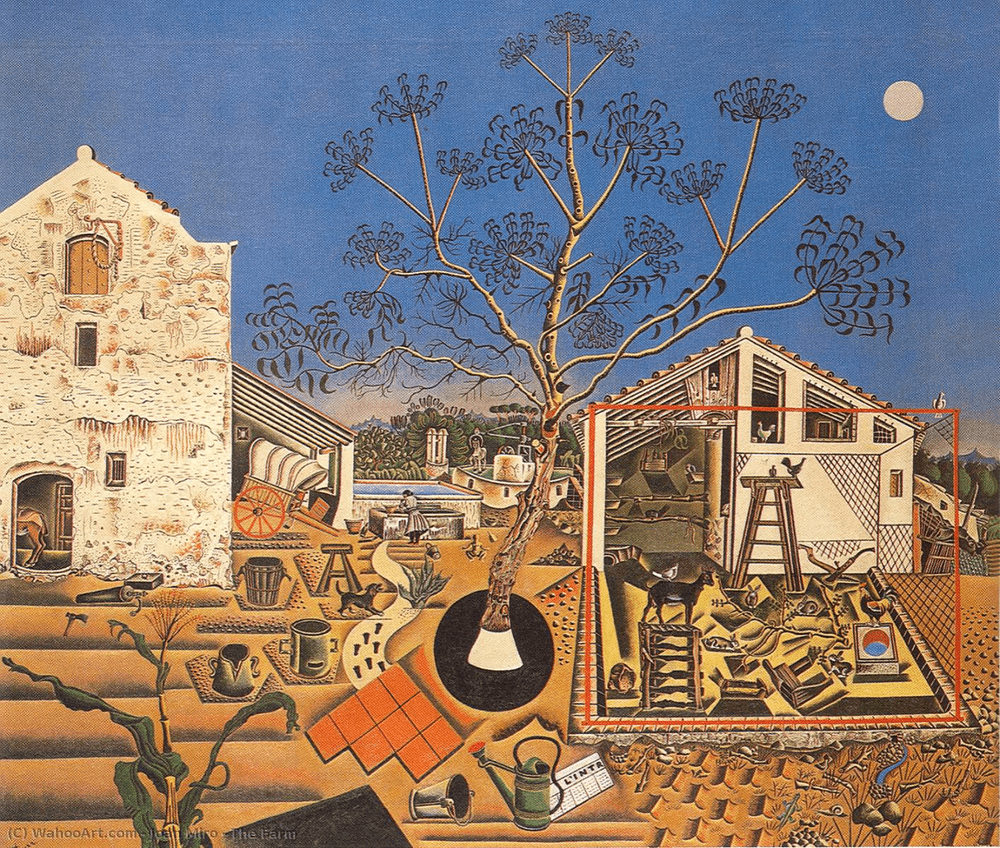

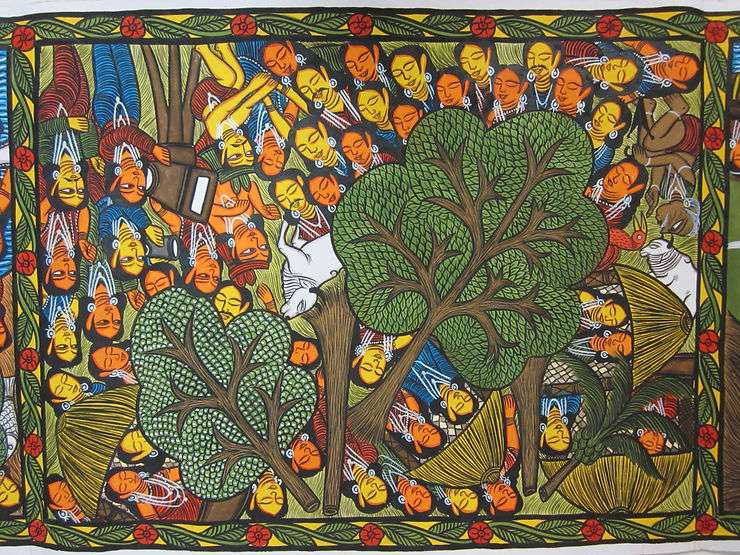

Meanwhile, folk art has been no stranger to depictions of nature’s wrath. Though varied in style and material, themes of floods, earthquakes, tsunamis and more, often find their way into folk art, chronicling cultural perceptions, fables and beliefs about nature’s fury. Take for instance works such as Gurupada Chitrakar’s Earth, Wind, Water, Fire: The Arts of Survival (2011). The Patachitra artist from West Bengal painted contemporary issues into his story-telling scrolls, as is seen in the depiction of the Haitian earthquake pictured above. He has also painted the Indian Tsunami, and Hurricane Katrina, amongst others. He would sing the stories of these scrolls as they were unfurled in a performative showing, which is a part of the Patachitra tradition.

Farther away from the Indian subcontinent (and also from our contemporary) are works such as Vesuvius in Eruption, with a View over the Islands in the Bay of Naples by Joseph Wright. This stunning depiction of both the eeriness and visual splendour of a volcanic eruption was created by the artist after his trip to Italy, where he observed the grandeur of the mountain and eventually painted thirty images of the Vesuvius. In the melancholic foreground of this painting, you can observe two men and a mourner carrying the body of a victim of the volcano. The addition of this element to the composition is an acknowledgement of humankind’s insignificance in the face of nature’s resplendent power.

Some artworks, however, more strongly foreground the human element of natural disasters. Like John Steuart Curry’s Tornado over Kansas (1929), which portrays the threat that the destructive force of a tornado poses to a family’s life. The distressed family is seen “picking up the essentials” and running for shelter, as the impending destruction whirls towards them uncontrollably. Curry’s religious upbringing and early life experiences greatly influenced his work—he was frightened of natural disasters since his childhood, lived through many storms, and was brought up with the belief that natural disasters were God’s punishment. His art has been regarded as his effort to understand and control these fears.

Another iconic painting that dissects the human frailty and terror when faced with nature’s wrath, is Karl Bryullov’s The Last Day of Pompeii (1830–1833). Like Joseph Wright’s work, this is also a depiction of Mount Vesuvius in eruption, albeit in AD 79 when the volcano consumed the city of Pompeii along with most of its inhabitants. It conveys the range of emotions that must have been experienced during one of the most legendary natural disasters in human history. The theme of the painting, as was common for the Romantics, is simply the sublime power of nature, and a reminder of our plight and insignificance in the larger scheme of things. No human, no man-made object or artifact, would survive.

What is it about gazing at such artworks that has prevailed as an experience across time and space? Regarding the suffering of other human beings, regarding the insignificance of our own lives and grandiose plans? What is the role of this work?

Perhaps some beginnings of an answer can be found in Susan Sontag’s words: “Compassion is an unstable emotion. It needs to be translated into action, or it withers. The question is what to do with the feelings that have been aroused, the knowledge that has been communicated. If one feels that there is nothing “we” can do—but who is that “we”?—and nothing “they” can do either—and who are “they”?—then one starts to get bored, cynical, apathetic.”

As our natural world deteriorates with each passing day, this “wrath” of nature, which is but a repercussion of our own unthinking actions, only grows more fiery. Whether these artworks and their continued creation serve as a reminder, a warning, or a channel for our own existential dread—they will continue to prevail until the end of our race, and hopefully, prompt some action that might in turn, prompt some hope for us.

Tell us in the comments about other artworks that depict natural disasters.