Have you ever wondered why people in old photographs don’t smile a lot? It’s not that they didn’t have their light moments, but rather the time taken to click a picture wasn’t as quick as it is today.

It isn’t surprising that at some point technology would have intersected the realm of another necessity – art. But how do we characterize a photograph as art? The solution lies not primarily with the photograph, but the photographer. The photographer is identified with the vision of an artist, with their photographs being their medium of expression – of a cause, a movement, a principle.

While the difference between the two may seem more dense than the similarities they share in articulation, it is their combination that is the densest of all. Let’s explore some causes that fine-art photographers from two contrasting generations of time and space have dedicated their practice to.

Preserving Negatives and Conserving Nature

Conservation has been a significant subject to the lenses of generations. It is not only the cause that draws light and shadow, but also preserves them. To identify what living means and let it come to the foreground was the mission of two individuals who found their muse in conserving the living and the still.

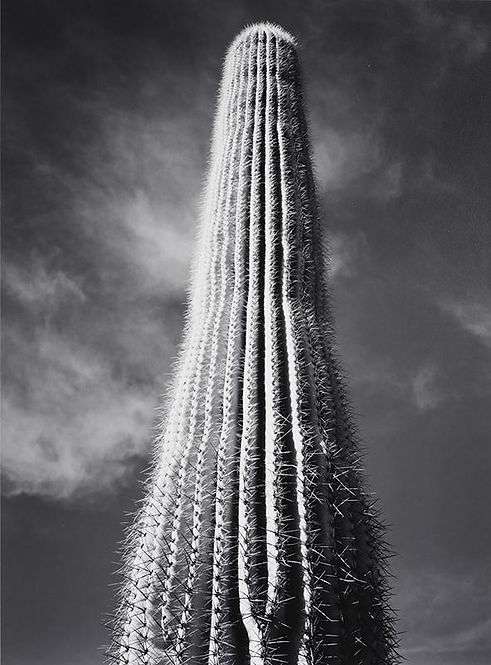

“Ansel Adams” and “landscape” are two entities that co-existed in the American West during the 19th century. Adams’ love for nature always ran ahead of his monochrome captures, not leaving a single stone unturned in green arms. His works expressed strong gratitude to the art of photography, from when he got his first camera at Yosemite National Park. From Pictorialism – a photographic technique to imitate paintings with soft shades and diffused light, to reflecting upon nature with murals and the rural tenderness of Moonrise – Adams brought nature to life.

And today, if the Western frontier has finally ceased to be pushed further, we have Vijay Sarathy continuing to push the boundaries that Ansel Adams chased a century ago. Observations in colour, visual rhyme schemes, and strong symbols amidst an artistic portrayal of landscapes are his instruments in bringing nature to life.

On blending romantic portrayals of nature with conservation, Sarathy says, “My work has always been about bringing out the latent poetry dormant within nature. I’ve always been intertwined with nature, being raised by the sea, and I’ve lately been realizing how much it has truly championed my life. I always get something profound and unspeakable when I’m in her company and this is what I try to channel into my work and try to make other people feel as well.”

As elusive as the environment of the past, his undying love for the hills and their sheltering are captured in a common narrative. As Sarathy weaves his photographs into specimens of an artist’s deepest emotions, he brings forth stories from a faraway land in reality.

The Gender Assignment

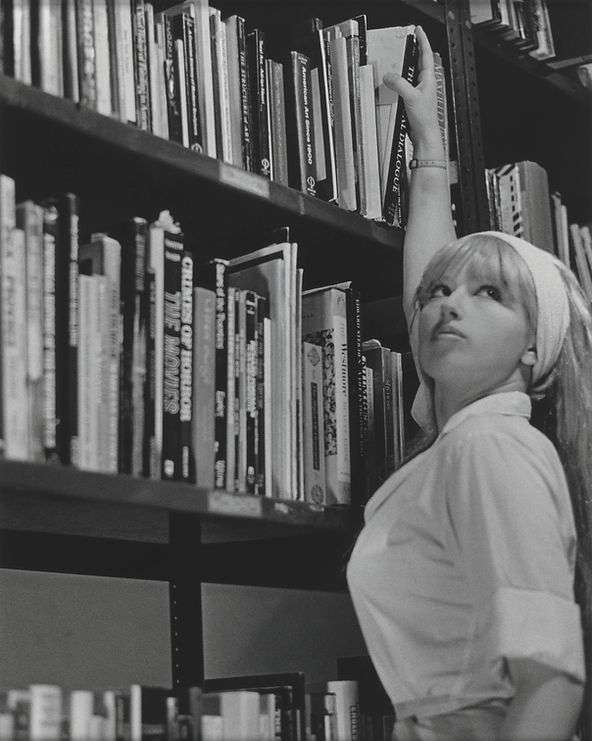

It is the year 1977. Amidst the growing rigidity of gender roles, a young lady called Cindy Sherman decided to bring attention to the suffocation her gender was experiencing in a society that had prescribed what women should do. Her awareness of these roles being assigned even before birth was a strong expression in her art.

She set out on a trajectory of Untitled Film Stills, where her parts, including “the office girl”, “the bomb”, “the librarian” and “the girl on the run” were captured across three years in the pattern of Film Noir. Through the darkness on a film screen, she recognized the prejudice and caught the eye of the art world. Her exaggerated portrayals delivered a straightforward message: stop telling women what to do.

30 years on, in 2007 the social experiment has been handed down to a community of women, and Yijun Liao looks at the modern dynamics of a woman and a man in a household. Beginning to explore her relationship with her partner, Liao took up a role like never before in various situations. A two-way social experiment between her audience and her took up a personal space of her residence and her artistic practice.

When asked about how she underwent the conscious realization of becoming a photographer, Liao says, “I worked as a graphic designer for three years before. I was very tired of always having to change my design by my clients…At that time, I watched a film called Blow-Up. I was simply admiring the photographer’s lifestyle in the film. That’s when I wanted to become a photographer. After studying photography, I realized that photographers are all different. I might never have the lifestyle I admired in the film, but it helped me to find my true self.”

Her photographs in Experimental Relationship struck the roots of gender and the cultivation of the concept over time. An unconventional combination of female superiority, nationality, and a heterosexual relationship took precedence over the instrument of her imagination and brought to the world an eternal process, resulting in discourses personal and societal.

The Filament of Social Change

A loud call towards the end of a street. Briskness of a thousand feet headed to the destination of change. Powerful flags of solidarity. The passion towards making a difference. A flashback.

Thomas Dworzak’s images have always been of substance to the idea of “revolution”. They don’t just define revolution in their own language, but also live inside it for a lifetime and contribute to it throughout. His camera is his weapon on the field and inside his thoughts. A strong essence of culture has been omnipresent in his work through thick and thin while giving him a channel to portray what he witnesses as objects behind his motivation to photograph. Dworzak is an experiential detective, who puts himself into the perspective of each party with an incomplete conscience, to blend into his own practice.

Close looking. Silent screams. Raw, intense, thought-provoking and thought-shattering visuals. Evidence of wrongdoing to support correction. A search for surviving legacy. The search for a better future. A reality.

Emily Garthwaite initiates an emotional and psychological engagement of her audience with the issue she conducts through her camera. In Light Between Mountains, she addresses unearthed atrocities in the setting of elevated land mines in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq and her experience in the location and the situation of human rights violation.

Not only do her photographs imply the recurrently threatful and alarming conditions to the environmental legacy of the region, but also to the communities that have preserved it with their lives. Garthwaite’s intention here is to visually preserve their voices until they reach the right of redressal, as a part of them.

We Know How the Caged Birds Sang

What all can a portrait depict? Rather, what all can a simple portrait betray about the person in the frame? For one, what it doesn’t show you is a game of chess.

The person’s life depends on that game of chess. The two ways you can go with – fighting, or flying – dictate how many moves you have left. And it isn’t long before all your moves are exhausted, leaving only one predicament – and flipping over the board isn’t an option.

This isn’t just an allegory for how we engage with death, but rather, how we engage with our mental health and the stigma around it – which is much more deadly. Gone are the days where gore and violence were responsible for the coming down of the scythe. As the clock ticks today, pain and sufferings have become much more subtle, hidden, and cryptic. With our prevailing attitudes, all we’ve been looking at is how to prolong the number of moves on the chessboard. But every now and then, we find people fighting.

The Surrey County asylum in the 1850s had the (only) pleasure of Hugh Welch Diamond’s presence. His was a peculiar brand of psychiatry, for he believed he could cure mental illness – by photography. For Diamond, photography offered a way of analyzing the depths of the human soul and bettered his idea of studying physiognomy: studying the patterns and contours of the face to analyze and treat their illness. What his photographs highlighted were the state of human affairs in the 19th century, and even after a good hundred and fifty years, highlight the subtle simplicity a smiling portrait hides, that of a morbid loom always hanging.

For Christopher Pereira, it is the vast expanse of the ocean over which this chessboard floats. His work The Shippy’s Paradise remarks the impact long durations of working at sea have on the shipmen in Goa. Talking about why the ocean has such an effect, Pereira remarks, “Loneliness. If you have ever spent an extended amount of time by yourself, alone with your thoughts – it can be extremely easy to think negatively, to question yourself and your decisions. This changes you and it can change the way your mind works…I always think about how sociable it is in Goa…Then suddenly, you spend six months at sea with limited social interactions. It’s an extremely tough job…”

It is remarkable to find Pereira adopting a minimalist approach in capturing such livid themes. The reason, he provides, lies in an experience with a friend of his who was battling depression. “If I wasn’t close with this person and he wasn’t speaking to me about it, I would never have known he was dealing with anything. Mental health problems can be found in anyone and this is the approach I took to the project. The minimalist approach I took to these portraits highlights the encrypted nature of mental health issues and how they often go unnoticed, especially in Indian communities where stigmas and misconceptions about mental health are still so prevalent.”

When Adam and Eve Switched Places

What these themes have highlighted here is the importance of narratives and how a photograph can be a lens of breaking established hegemonies, worldviews. Perhaps then, Donna Gottschalk’s documentation of the 1960s eloquently fights the case for fine art photography and its social significance.

In the exhibition Brave, Beautiful Outlaws: The Photographs of Donna Gottschalk, curator Deborah Bright notes, “It is extraordinarily rare to find such lovingly and artistically made photographs of lesbians from those years when homosexuality was widely criminalized and lesbians were portrayed in popular media as predatory, suicidal freaks. Where society saw monsters, Gottschalk saw heroes and she wanted to visualize the beauty and nobility of those who refused to live a lie.”

Photographs held a special value for Gottschalk. She used to click people’s photographs because she found people beautiful as they were, and felt that death loomed around every corner – so a photograph of those people would be her memory of theirs when she’d get old.

Similarly, Savana Ogburn’s work Eve questions the cisnormative narratives that have shaped our worldview for centuries: Beauty and the Beast, Romeo and Juliet, and her own focus, Adam and Eve. Christianity, for all its all-loving idea, has negated the presence of a Trans identity, that it’s meddlesome with creation. Ogburn repurposes Adam and Eve’s story by depicting it with queer protagonists, altering the story in itself – the story implies that God cursed humanity with Gender, not Sin.

Interestingly, the depiction isn’t to be noticed as anything provocative – and why not? After all, the imagery isn’t executed to get a reaction from the (conservative) community, but rather to simply highlight that Trans identities exist in the world, and should be permeating stories all across the board. And as her collaborator, Iv Fischer remarks,

“Who says Adam and Eve weren’t two trans folks frolicking in the Garden of Eden, beating their faces, and braiding each other’s hair?”

Gaspard Felix Tournachon has probably had the biggest footprint in the world of photography when it was growing from its nascent stage. While Nadar, as he was known, focused more on portraits, his fashionable portrait studio in Paris was also the site of something monumental in 1874 – as it was here that the Impressionists held their first exhibition.

This convergence of art and photography probably became one of the first instances behind people questioning ‘what makes photography art?’ Photography wasn’t now all about capturing in-the-now moments, but expressing an idea, an emotion. The arenas of life we’ve highlighted here are just a few in a several line of spaces where fine art photography is bringing evocative changes. As digital art permeates the social fabric more and more, photography as a fine art is destined to achieve even greater strides.

With a glimpse of how Fine-art Photography portrays causes, let us take you to Bengal’s mangrove islands and explore how they’ve inspired other visual narratives.