About 40,000 years ago, prehistoric painters endeavoured to create the first palette of pigments: ochre, red ochre, umber, bone black, and lime white. These are referred to as earth pigments, made from soil, burnt organic material, chalk and animal fat. Since their discovery, the history of colours has seen increased ingenuity as well as risk, in the ways humans have sought to create vibrant lasting hues for their art and artefacts. From crushed bugs, cow urine and a pigment made from arsenic that may have poisoned a famous historical figure, the stories behind some of the most iconic pigments in art history are as fascinating as they are unexpected.

Paintings in rock shelter 8, Upper Paleolithic period, Bhimbetka, India. Courtesy Bernard Gagnon.

Anthony van Dyck, Portrait of Agostino Pallavicini (ca. 1621). Oil on canvas, 216 x 141 cm. Courtesy Getty Center.

Seeing Red: The History of Two Pigments

Evidence suggests that red ochre, a pigment found in iron-rich soil, was in use in Africa around 300,000 years ago, which coincides approximately with the emergence of Homo sapiens. Studies indicate that the pigment has been used widely across the world at different times in history. In the Renaissance period, red ochre was used in painting panels and frescoes. In the 16th and 17th centuries, another red pigment gained prominence – carmine red, a dye produced from a cochineal insect, a parasitic insect that feeds on prickly-pear cacti native to Mexico and southwest United States. The process of harvesting and producing this dye was practised by the Mesoamerican peoples in southern Mexico, as early as 2000 BCE. When the Spanish conquistadors returned to Europe with the pigment, its vibrant colour created high demand among artists and patrons of the arts, making it the third most valuable import from the New World after gold and silver. Famous artists like Raphael, Rembrandt, and Rubens used ground-up cochineal insects as a glaze to enhance the intensity of other red pigments like red ochre. Even today, cochineal extract is used to produce red dye for cosmetics like lipstick and blush.

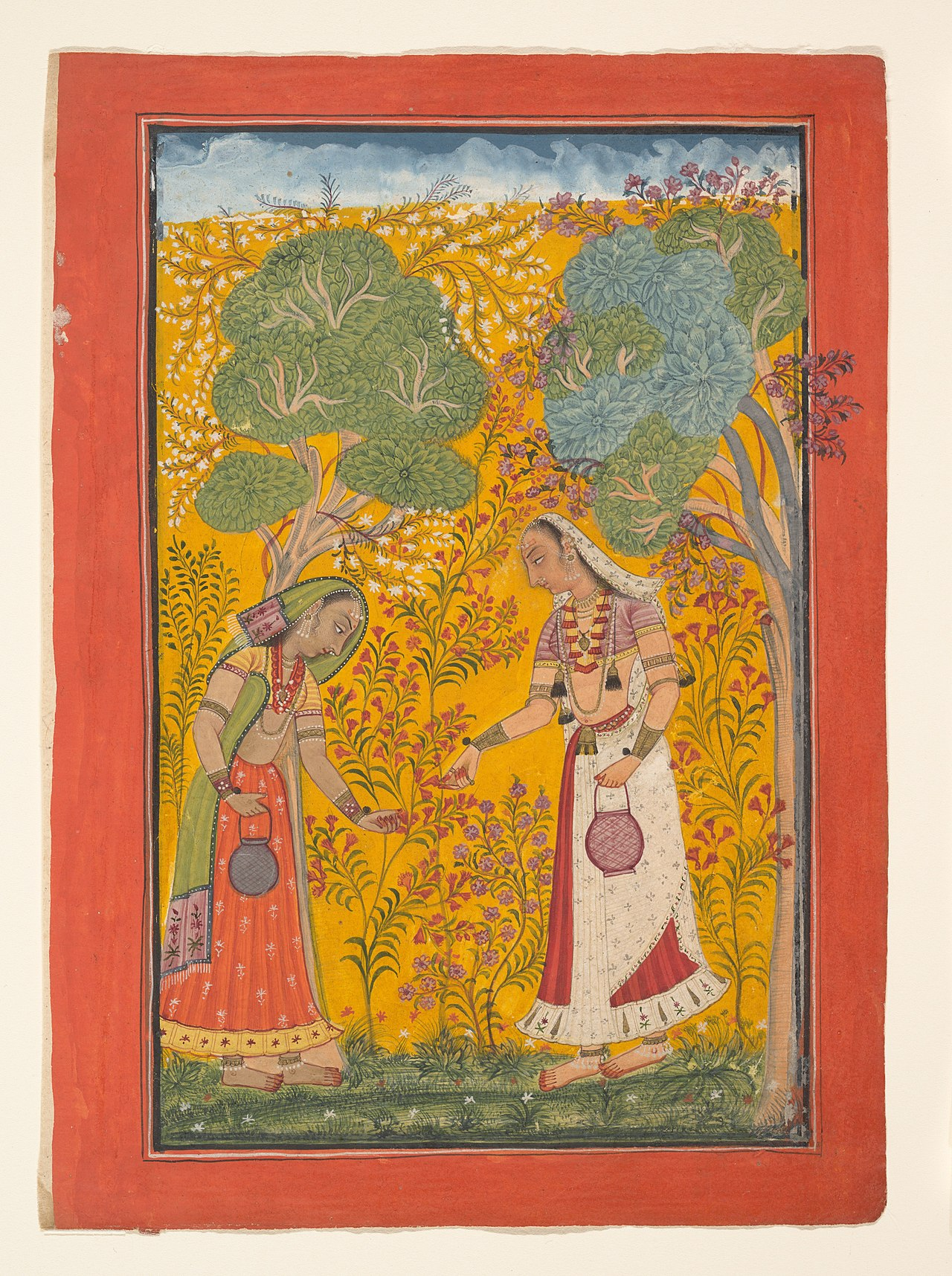

Vasanti Ragini, Page from a Ragamala Series (ca. 1710). Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper, 21.6 x 15.6 cm. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night (1889). Oil on Canvas, 73 x 92 cm. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art.

The Rise and Fall of Indian Yellow

Ragamala paintings, depicting the mood of a range of musical melodies or ragas, became popular in the late 15th century as the subject of Indian court paintings. In them, yellow was used judicially to depict a sunny landscape. This pigment is known as Indian yellow, and was produced by a small sect of gwalas (milk-men) in the city of Monghyr, present day Munger in Bihar, India, that were fed nothing but mango leaves and water. The cow urine was collected in terracotta pots, and clarified to a thick consistency over an open flame. It was then filtered, dried and clumped together into balls known as piuri or puree. The pigment was also used to dye fabric and paint walls. Subsequently it was brought to Europe via merchants in Calcutta between the 16th and 17th century, reaching the palettes of the likes of Vermeer and Van Gogh. In his Starry Night, Van Gogh blended Indian yellow and zinc yellow to create the bright luminescent moon. Mistreatment of the animals was perhaps the reason for the colour being banned, and it vanished from use by the early 20th century.

Egyptian faience, Hippopotame (Hippopotamus), (ca. 3800-1700 BC). Courtesy Musée du Louvre.

Giovanni Battista Salvi da Sassoferrato, The Virgin in Prayer (ca. 1640-1650). Oil on canvas, 73 × 57.7 cm. Courtesy The National Gallery, London.

Beyond the Blue Horizon

Egyptian blue was first produced in Ancient Egypt ca. 2,200 BCE, around the same time the Great Pyramids were built. It is considered to be the first synthetic pigment to ever be produced. Limestone, sand and a copper-containing mineral (such as azurite or malachite) were heated together at high temperatures, to produce an opaque blue glass. This could be pulverised and combined with egg whites, glue, or gum, and applied as paint or ceramic glaze. The pigment came into prominence throughout the Roman Empire, but the emergence of newer blue pigments caused it to fall out of favour and the production method was forgotten over time. In 2006, the conservation scientist Giovanni Verri accidentally rediscovered the process to produce Egyptian blue. Another blue, ultramarine or true blue, made from the semiprecious gemstone lapis lazuli, first appeared in Buddhist frescoes in Bamiyan, Afghanistan in the 6th century. Around 700 years later, this prized pigment made its way to Venice, where it quickly became a highly coveted colour in Medieval European art. Ultramarine, meaning ‘from beyond the seas’, was as expensive as gold leaf, making its use limited to significant figures like the Virgin Mary and appeared in exclusive commissions by the church.

Sandro Botticelli, Detail from Mystic Nativity (ca. 1500). Oil on canvas, 108.6 x 74.9 cm. Courtesy The National Gallery, London.

John Todd Merrick & Company, London, Wallpaper using Scheele’s Green (1845). Courtesy Crown Copyright.

Green Light, Red Danger

Verdigris was the most brilliant green readily available to painters. In the Middle Ages and during the Renaissance, artists commonly manufactured verdigris by hanging copper plates over boiling vinegar and collecting the crust that formed on the metal. The name comes from an old French term, ‘vert-de-Grèce’ meaning green of Greece. It is also sometimes known as copper green or earth green. By the end of the 19th century, the toxic Scheele’s Green had almost completely replaced older green pigments derived from copper carbonate. The vibrant green pigment was accidently created in 1775 by the Swedish-German chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele. It was made by heating up sodium carbonate, adding arsenious oxide, and stirring until the mixture was dissolved, followed by the addition of copper sulphate. The poisonous Scheele’s green was not just used in dyes and paints, but also in wallpapers, insecticidal sprays used on vegetables and postage stamps. The pigment is known to have played a role in the death of Napoleon Bonaparte – who lived in a room painted brightly green – as traces of arsenic were found in his hair.

The silk shroud of Charlemagne made with gold and Tyrian purple (9th century). Courtesy Musée National du Moyen Âge, Paris.

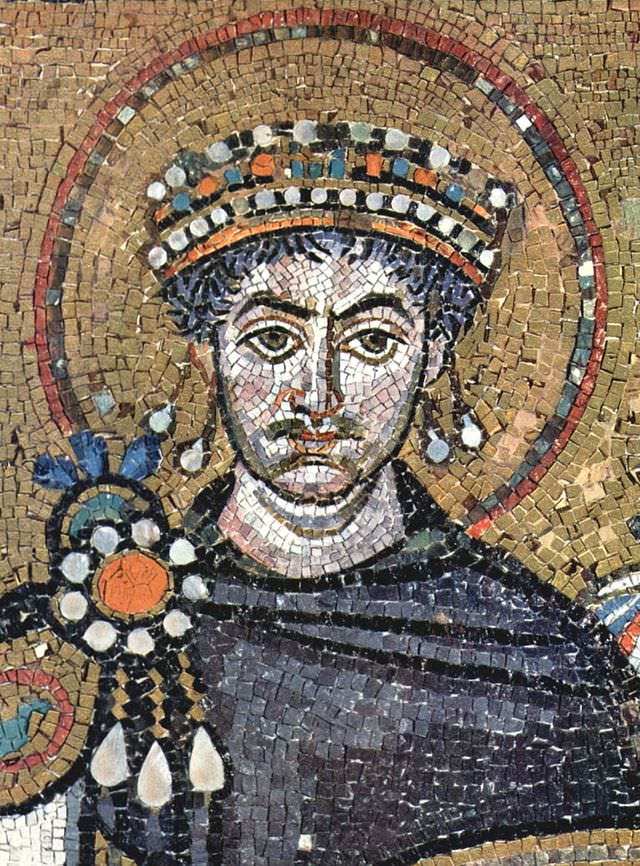

Detail from Portrait of Justinian I in the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna (ca. 527 to 565 CE). The emperor is shown wearing a Tyrian purple robe.

Purple Reign: The Beauty and Terror of Tyrian Purple

For thousands of years, Tyrian purple was the most valuable colour available – worth more than three times its weight in gold, according to a Roman edict issued in 301 CE. Subsequently, the colour was used by artists to symbolise wealth and royalty. Some Roman emperors are said to have decreed that the penalty for anyone using the colour – other than themselves – would be death. The colour was extracted from the mucus produced by sea snails in the Murex family, and it could take up to 10,000 snails to produce a single gram of dye. Tyrian purple could be produced from the secretions of three species of sea snail, each of which made a different colour: Hexaplex trunculus (bluish purple), Bolinus brandaris (reddish purple), and Stramonita haemastoma (red). Once collected, the mucus was harvested, and in some cases the mucus gland was sliced out with a special tool; although the exact process of extracting the colour is undocumented and remains obscure. The colour appears in Phoenician mythology when Tyros – the mistress of Melqart, the patron god of Tyre, present day Lebanon – and her dog were strolling along the beach. The dog’s mouth appeared to have been stained purple after biting into a washed up mollusc, and upon seeing this Tyros demanded a garment dyed in the same colour, thus began an industry.

A Journey Through the Spectrum

The evolution of pigments throughout history showcases humanity’s relentless pursuit of vibrant hues for artistic expression, from prehistoric earth pigments to the unusual and morally questionable processes behind iconic colours like Indian yellow and Tyrian purple. These pigments, sometimes fraught with unexpected consequences, have left an indelible mark on the history of art, and reflect the colonial underpinnings of trade and art production. Today, a time of emulsions, glossy enamel, ready-made and accessible colours, this historical labour of creating a pigment for the canvas has become a forgotten archival practice. Due to scientific developments and the demand-supply chain, we are far removed from the ochres, verdigris and Tyrian purples of history. However, indigenous artists such as Camas Logue, from America, Sarah Hudson from New Zealand, English artists Caroline Ross and Tilke Elkins who started the Wild Pigments Project, are collecting dirt, clay, rocks and flowers and turning this organic material into works of art. This cyclic return to earth pigments is a sustainable way to produce pigments from natural sources, and perhaps also a decolonial effort towards healing the earth from the harsh effects of industrialisation. Maybe slowing down and rethinking art production might pave the way for something enduring to emerge?