In today’s fast-paced and technology-driven world, love has become a commonplace and often fleeting experience. From dating apps that promise instant gratification, to instant messaging platforms that enable communication with multiple potential partners, the quest for love has undergone dramatic transformation. Amidst this ever-changing landscape, it’s fascinating to reflect on how love has been portrayed in art over the past two centuries. From Cupid to Calle, what can the world of art tell us about what love looks like?

Antonio Canova, Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss, (1793). Marble and Metal, 155 x 168 x 101 cm. Courtesy Jean-Pol GRANDMONT/Wikimedia Commons.

In this 18th-century sculpture by Italian artist Antonio Canova, the mythological lovers Psyche and Cupid are gazing intently at one another. Canova’s work portrays the scene after Cupid revives Psyche with his kiss, a pivotal moment in their complex love story in Roman mythology.

Despite the bizarre circumstances of their relationship – Psyche is married to Cupid but forbidden to see him, although he visits her bed at night – the sculpture captures their tenderness towards one another. Their tale also involves a jealous Venus, Cupid’s mother, who orders Psyche to undergo three seemingly impossible trials, one of which sends her into a deep death-like sleep. Cupid, taking on a heroic role, ultimately rescues Psyche.

The sculpture is representative of how love was represented in art two centuries ago, often infused with mythological narratives and themes of forbidden desire. It also reflects the renewed interest in classical mythology at the time, as part of the broader revival of classical culture. This movement, known as neoclassicism, influenced many artists who sought to revive and reimagine ancient myths and legends in their work.

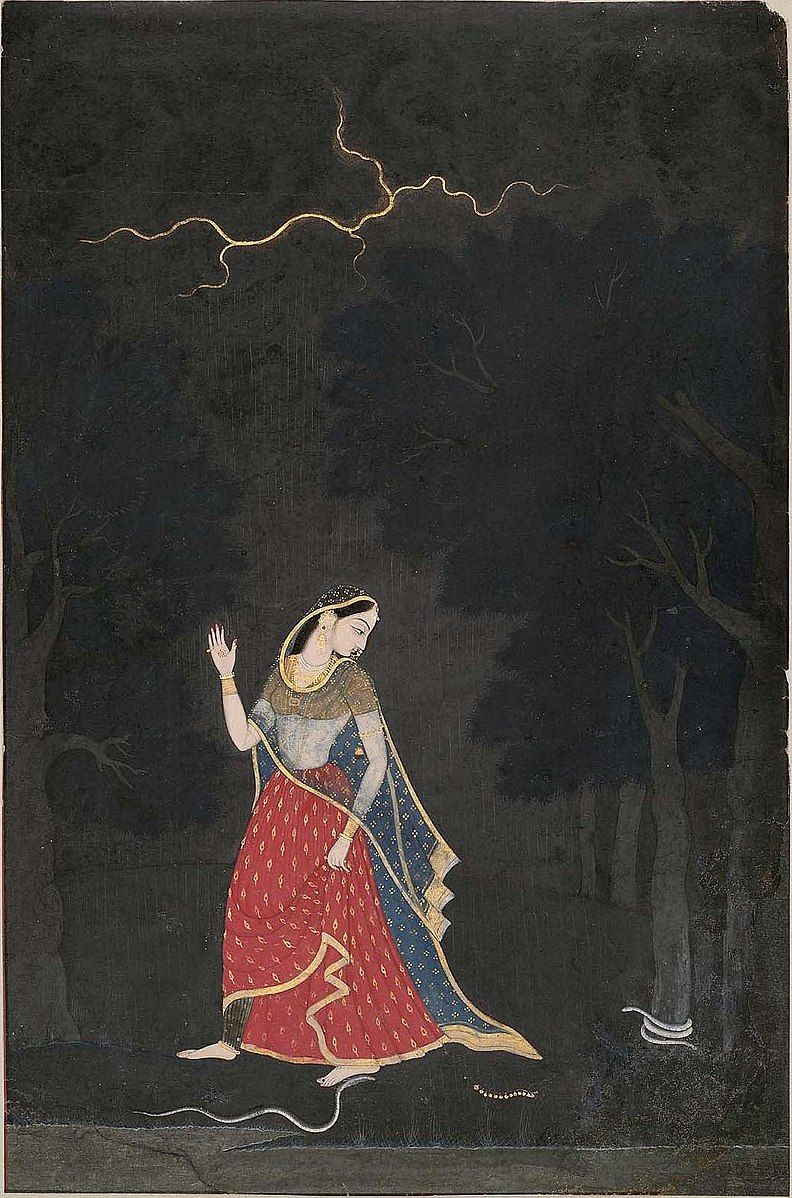

Mola Ram Singh, The Heroine Going to Meet Her Lover at an Appointed Place, (ca. 1800).

Gouache and gold on paper, 15.24 x 20.32 cm. Courtesy MFA Boston Collection.

What lengths we go for love. In this folio by Mula Ram Singh of the Kangra school of painting, the archetypal Abhisarika Nayika, or the female protagonist who goes to meet her lover, is walking through what appears to be a forest. The dark night tests her love, but neither the threat of snakebite, fallen jewels or rain can stop her from meeting her waiting lover.

The painting is inspired by a 16th-century Braj-Bhasa text, the Rasikapriya (Connoisseur’s Delights), composed by Keshavdas, the court poet of Kunwar Indrajit Singh and Raja Bir Singh Deo of Orchha, present-day Madhya Pradesh. The text enumerates the eight archetypal male and female lovers (nayakas/nayikas) and their corresponding emotions and encounters. Keshavdas’ Abhisarika Nayika, braves thunder, lightning, thorns, snakes, and other creatures of the forest, in an effort to keep her rendezvous. Today’s Abhisarika Nayika has the Uber app at her disposal, and her nayaka has probably left her on read.

Edvard Munch, Separation, (1896). Oil on canvas, 127 x 96 cm. Courtesy Munch-museet, Norway.

The Norwegian painter Edvard Munch’s ‘Separation’ is probably what ghosting feels like. The two main elements in this painting are a man dressed in black, (perhaps Munch himself) clutching his heart, and a woman faced away, whose hair is flowing in the wind and entangling with the man’s heart. The gold paint in the woman’s hair elevates her to an almost divine or other-wordly character. It seems that despite his unrequited love, he can’t seem to let go and move on. Sorrow seems to blur the shapes in the painting, everything is bleeding. How long will the one that got away stick around?

Felix Vollaton, The Lie, Intimacies I, (1897). Woodcut, 18.1 × 22.5 cm. Courtesy The Met.

This woodcut print, part of Swiss-French painter Felix Vollaton’s ‘Intimacies’ series, seems to be nothing out of the ordinary, however, the title suggests otherwise. A couple are seated on a sofa in an amorous embrace, they are perhaps at either one of their apartments in Paris, having just drunk a cup of tea before getting decidedly distracted. Vollaton often depicted the insidious nature of relationships, and reflecting on the title, – ‘The Lie’ – the whole image takes on something of a dark air. Who is the liar? Are they having an illicit affair? Or is the pretence of their love “the lie”? It serves to remind us that love and betrayal are on either side of the same coin, and the fools among us will always try their luck.

Gustav Klimt, The Kiss, (ca. 1908). Oil and gold leaf on canvas, 180 cm × 180 cm.

This iconic painting by the Austrian painter Gustav Klimt is straight out of a fantasy or daydream. Klimt’s visits to the Byzantine Church of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy, had a profound influence on his work, leading to the development of what was later referred to as his ‘Golden Period.’ This period is characterised by the extensive use of gold leaf, as seen in his famous painting ‘The Kiss,’ which incorporates the intricate patterns and rich textures inspired by the church’s stunning mosaics. The painting’s golden hues gives the impression of a hallowed coupling and elevates this ordinary kiss, to a divine ethereal embrace. Despite the changing landscape of romantic and artistic expression, ‘The Kiss’ remains a timeless testament to the transformative and eternal nature of love.

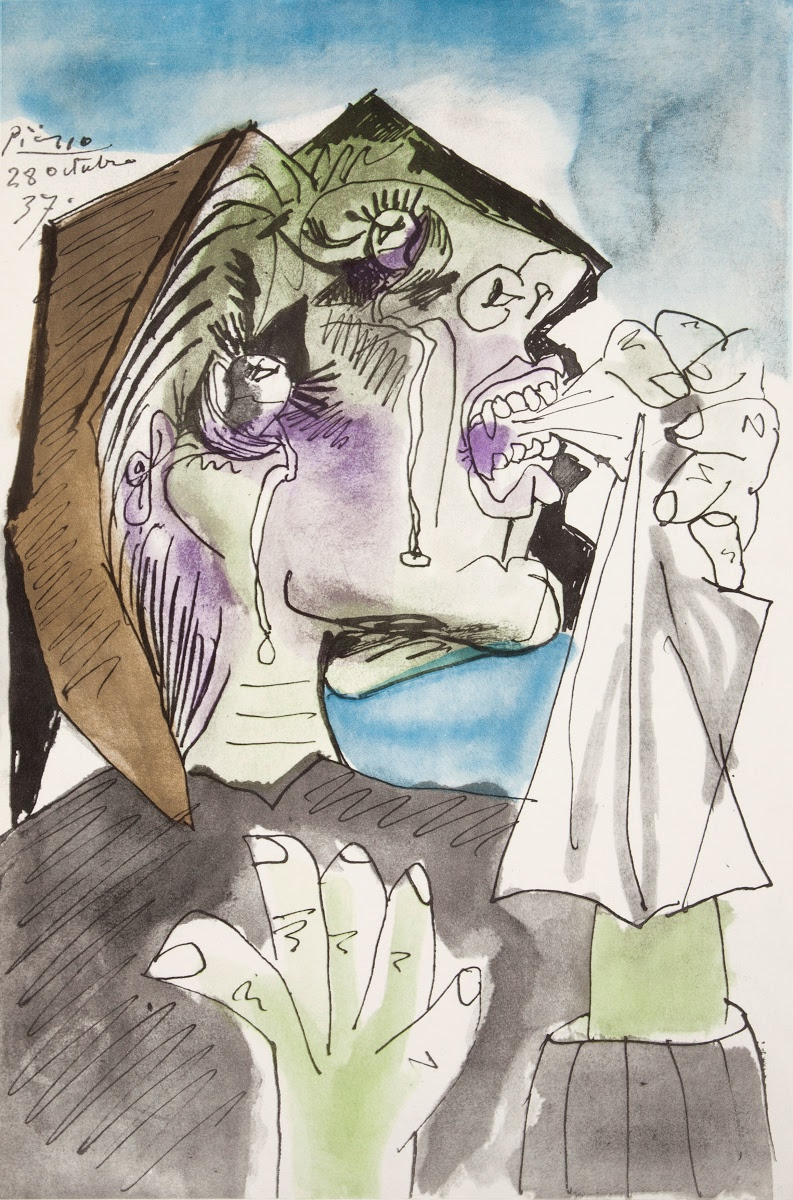

Pablo Picasso, The Weeping Woman, (1937). Lithograph on paper, 50 x 36 cm. Courtesy Contemporary Art Platform, Kuwait.

‘The Weeping Woman’ or La Femme Qui Pleure, is said to be Spanish painter Picasso’s thematic continuation of his acclaimed painting ‘Guernica’ that raised awareness about the Spanish Civil War. Although ‘The Weeping Woman’ cannot be considered an anti-war symbol, it transcends its historical context, speaking to universal experiences of loss and heartache. Love, like war, can have devastating consequences, leaving individuals feeling shattered and alone. Both love and war have the power to shape our lives, test our resilience, and reveal our true character. They are formidable forces that can profoundly impact our emotions, forcing us to confront our vulnerabilities and summon our inner strength.

Nan Goldin, Warren and Jerry Fighting, London, 1978 (2019). Inkjet photograph on paper, 25.9 × 39.3 cm. Courtesy Tate, UK.

American photographer and activist Nan Goldin is known for her candid, raw, and unflinching photographic style that captures intimate moments of love, friendship, sex, and drug use within subcultural communities, particularly in the LGBTQ+ scene of New York City in the late 1970s and 1980s.

‘Warren and Jerry Fighting, London, 1978’ is one of ten prints from Goldin’s series ‘Skinheads and Mods’, that documents members of opposing youth-culture groups known as ‘skinheads’ and ‘mods’. Goldin’s photograph captures a tenderness and almost erotic intimacy between Warren and Jerry, akin to Shakespeare’s fated lovers Romeo and Juliet. The skinheads and mods may have been at odds with each other, but Goldin’s lens reveals a moment where two individuals, caught in the midst of a cultural divide, are united.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “Untitled” (Perfect Lovers) (1987-1990). Wall Clocks, 34.29 cm. Courtesy Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation.

What do you do when you and your significant other are out of sync? This installation by Felix Gonzalez-Torres consists of two identical, round wall clocks hung side by side. At the time of installation, their hands are perfectly aligned to tell the same time. Oftentimes, by the time the exhibition opened, the clocks would fall out of sync, by seconds or even minutes. It may be read as a metaphor for partnership and love, and the sometimes inevitable symptom of drifting apart over time. Like clocks, we too can find each other’s rhythms once again, despite the distance. If only it were as simple as winding a clock.

Sophie Calle, Take Care of Yourself, (2007-2009). Multimedia installation. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery

‘Take Care of Yourself’ is a multimedia installation that the French artist Sophie Calle created in response to a breakup email she received from her former partner, whom she refers to as ‘X’. The work explores the themes of love, heartbreak, and the complexity of endings. It also nudges at the comedy of breaking-up over email.

Through a series of interviews with various individuals, including women from different professions and nationalities, as well as a group of teenage girls, Calle sought to understand and deconstruct the letter’s meaning and her own feelings. It makes visible her labour of love.

The strength of the work is derived from the collective response to individual loss and the plurality of a universal experience. It suggests that a fulfilling life is indeed possible after love, it’s been done countless times.