Most closely identified with the New York School of painters, Mark Rothko is just as enigmatic now as he was in the late 1940s when his glowering paintings catapulted him into fame. Still attracting controversy, like most avant garde artists of his generation, he deftly provokes his viewers and critics who always have polemical opinions about his vast, electrifying canvases. “A painting is not about an experience.” he maintained, “It is an experience.” That could be said about art in general, and we couldn’t agree more! We are here to guide you through that experience as we take another look at the meandering progression of Rothko’s artistic genius.

Here at Art Fervour, we are continually trying to distill what separates art from ‘non-art’, especially in bewildering times of constant change. As it is the aesthetics of abstraction often bring out disappointment in the passing observer who claims the artist whose work they don’t ‘get’ to be a fraud. Adding insult to injury, a common criticism of art, abstract art especially, comes from people who claim “even a child could do it”. Mark Rothko has been a strongly polarizing figure, famous for his towering colour fields of canvas alternating with panels of monochrome feathering into the background. Famously unapologetic and reticent, Rothko wasn’t (and still isn’t) a prey to the quickly labeled and forgotten, discarding all art movements ascribed to him, rejecting superficial flowcharts of interpretation, and most distinctively positioning the viewer to draw them in and experience the flux of movement within rather than telling them what they should be seeing.

The cliché of a misunderstood, chain-smoking, alcoholic genius also plagues Rothko’s reputation with many of his critics quickly explaining his transition from the use of bright to dark colours as the progress of his deteriorating mental health and eventual suicide. But these easy generalizations are insulting to Rothko’s body of work, his technical dexterity, and his far-sighted understanding of art. An offshoot of the American Dream, as much as he would resist, public perception thrived on intertwining his life and art.

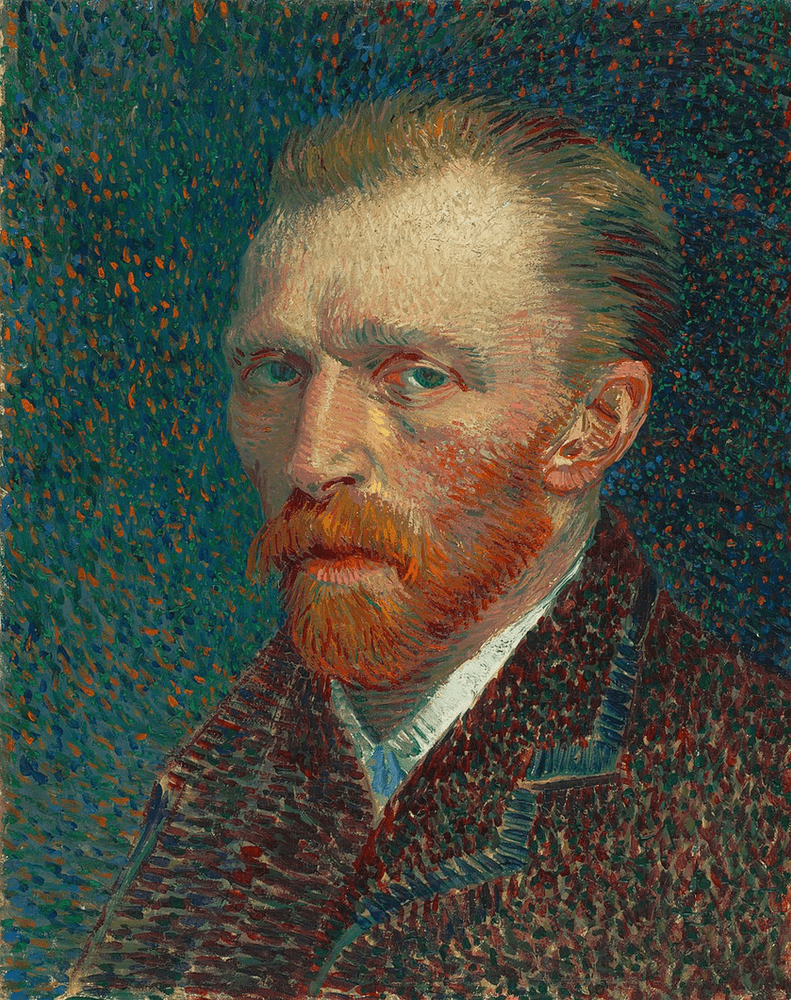

A portrait of the artist as a young man

Born in 1903 into Jewish family in Russia, Rothko’s childhood had been plagued with anti-Semitic pogroms which had forced his family to immigrate to Portland. Various biographers have focused on his troubled transition into adulthood, commenting upon his early encounters with elitism and racism which had led him to drop out from Yale. This could be recognized as his first foray into anti-establishment ideology and his subscription to leftist thinking, railing in support of workers’ rights in the industrial milieu. His first brush with anarchism and radicalism through Emma Goldman’s lectures also helped him defend his Surrealist influences later in his career. Attending the Parsons New School of Design, New York in 1923, Rothko finally found his mentors and friends of like-minded amiability focusing on Modernist art, with whom he went on to form a collective and exhibited his first paintings to a lukewarm reception. His family had resented him for picking up an unconventional profession with poor returns as money had been tight with the death of his father and his mother’s job as a cash register operator. In the backdrop of the Great Depression of the 1930s, being a professional artist would have been considered suicide, especially for Rothko’s underprivileged upbringing. Having sustained himself with working as a newspaper deliveryman and a busboy, Rothko had no qualms dedicating himself to intense labour, which he continued through exhibitions in the US and Europe, gaining respect from his peers and critics who could recognize his authentic stylistics within the bell jar of Modernism.

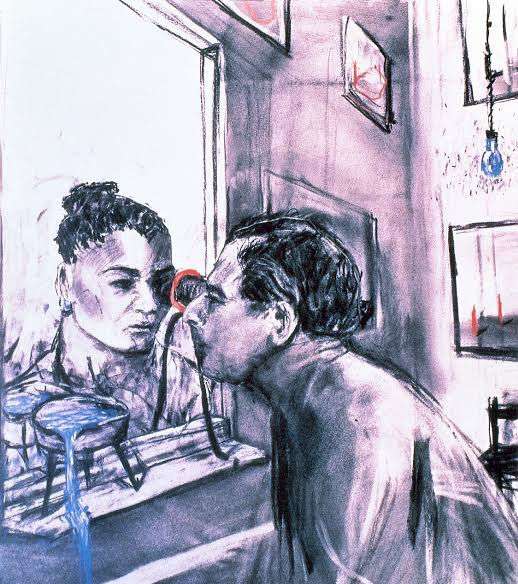

A forgotten shore

As a fledging artist with a distinctive individuality, Rothko’s critics especially concentrated on his figurative oil paintings, often of cityscapes and interiors featuring people in loose faceless outlines, strongly reminiscent of Cezanne’s domestic subjects. A particularly fascinating series composed by him in the 1930s depicted scenes from the New York subway where tall, ghostly New Yorkers lounge about and wait, insulated as if in their silence, playfully portrayed with modestly contoured figures- anonymous, expressionless, and seemingly preoccupied with their daily dispositions. He had no patience for the realistic aspects of portraiture, but rather focused on the emotional responses to alienation and despairing loneliness. An early fan of Edward Hopper, Rothko had composed some paintings as homage to him. Whereas Hopper had put a face to the isolated American subjects, Rothko defined the universal saturation of failure to develop human connections, even fleeting, in a largely withdrawn world within their immediate surroundings through a seamless blending of Expressionism and his prior Surrealist influences. The despair was to be suggested through their postures, their distancing, and never prescribed as he dismissed the literal interpretations of his art. These abstractly figurative artworks are often overlooked in favour of his more enigmatic paintings of colour-fields later on in his oeuvre which definitely are more acclaimed and coveted, but his early paintings do display his range and the scope of his journey to figure out his peculiarly characteristic style, with various pit stops along the way.

Art as Tragedy

1940s onwards, however, his increasing disenchantment with Expressionism and his then contemporary urban subjects led him to abandon this style and move on to psychoanalytically inspired paintings dealing with mythical symbols and motifs. His earlier compositions couldn’t accommodate his new interest in experimenting with colours and forms, and hence his search for newer subjects came to be guided by Nietzsche remarking upon the lack of mythology of modern life. This new stage of his work had also been majorly inspired by his readings of Freud and Carl Jung combined with scenes from Classical Greek tragedies and the Bible via vague animal shapes which critics had termed mythomorphism. Proclaiming himself a modern mythmaker, Rothko condensed his interest in the tragedy as the “simple expression of the complex thoughts” in a manifesto he co-wrote with Adolph Gottlieb. Published in The New York Times, this was probably his first public vocalization of his scorn for the art market which would make commodities out of art and was “spiritually attuned to interior decoration”.

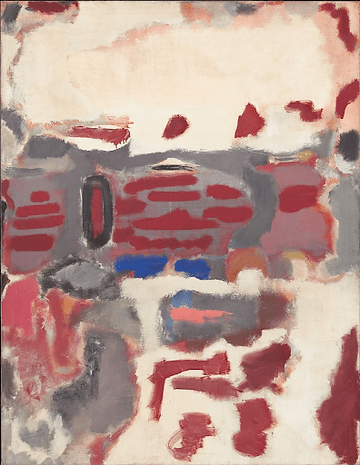

Shades of red

Maintaining his penchant for the dramatic and tragic, Rothko abandoned his symbolist thought of his Surrealist biomorphic paintings, and finally began to just experiment with abstractions. The products of a transitional phase which his critics termed as multiform paintings, these compositions were crumbling blocks painted in unevenly interrupted and patched distributions. A style which would later contribute directly to his mature work, the multiforms firmly seemed to reject any representational shapes that could be used to describe them. The distinctively contrasting colours used contributed to a pulsating effect which he had claimed to be the organic expression of human emotions. This period of intense activity also coincided with him extensively writing about art which was compiled by his family and published posthumously in 2004.

Colour fields, ahoy!

The end of the 1940s saw Rothko established in his signature style now recognized at first sight as his in various galleries and museums around the world through perfectly aligned rectangular panels with diffused boundaries seemingly arising from a monochrome background. Akin to a controlling stage director, Rothko had prescribed the viewer to be 18 inches away from the canvas in order to fill up their peripheral vision to actually engage with the art work and be enveloped in them, creating a sense of awe and transcendence. His later paintings were exhibited with the instruction of hanging them low so that the viewer could completely face them, removing all hints of representational art mimicking the world outside of his painting. There was to be dim lighting as well, shrouding them in enigma. The viewer was to be of primary focus- the viewer’s interior emotional life was to elicit the responses to the painting within an almost claustrophobic environment. He aimed to protect his art, especially from critics who accused him of being a self-aggrandizing charlatan and the general population who craved his paintings to be hung up above a fireplace “tying up the room”. Painting was a religious experience for Rothko, and he wanted the same for his audience. He guarded the recipes of the composition of his paints even from his assistants, and only later ultraviolet analysis of his paintings would reveal a myriad range of ingredients used: eggs, glue, and formaldehyde among others, mixed in oil paint. Painting translucently several layers on top of each other, Rothko achieved complex shades with sweeping brush strokes with a wall painter’s brush.

The brush is mightier than the pen

Despite positioning himself as an “eternal pessimist”, Rothko has established himself as the toast of the art world since the 1970s. The sale of his paintings dredged up millions of dollars, making him one of the most coveted and expensive artists in art history (see if you could spot his work in one of your favorite TV shows here). Whatever his grudging critics might say about him, Rothko provokes the reactions he wanted. People break down in front of his paintings, awed by an enveloping feeling of sublimacy and flinching at his intensity. The Rothko Chapel in particular housing 14 of his final paintings draws in thousands of visitors each year- these final paintings continue his brooding preoccupation with administering transcendence, while staying off bright, chirpy, and exuberant colours of his 1950s paintings. Concoctions of black, maroon, rust, burgundy, and purple adorn the simplistic octagon, punctuated with gutters of white walls with low, diffused sunlight. This probably best encapsulates the legacy of the sensitive artist, humming along to his favorite records of Mozart and Schubert while cooking up yet another storm to take up the art world.

In the 2009 play Red, John Logan has his fictionalized version of Rothko confessing that he was afraid one day the black will swallow up the red. But we all see you, Mark, we can see the red still.